Predictability is the Point

Designing Agentic Systems with Good Habits: Mature Expectation

The “Demo” Trap

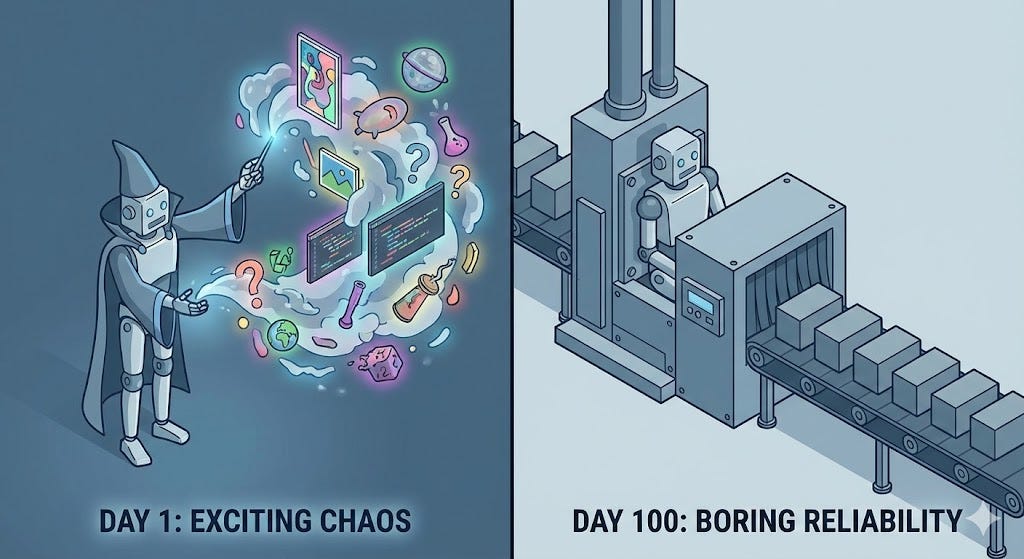

There is a specific lifecycle to most agentic systems.

Day 1 (The Demo): Everyone is amazed. The agent takes a vague instruction, reasons through it, and produces a result. It feels like magic. The stakeholders say, “Look how flexible it is!”

Day 100 (The Hangover): The engineering team is exhausted. That same “flexibility” means the agent never solves the problem the same way twice. Debugging is impossible because the logic changes with every temperature setting. The stakeholders now ask, “Why can’t it just do what it did yesterday?”

We often confuse Capability (what the model can do) with Reliability (what the system will do).

In the early days, we equate progress with “more autonomy.” We want the agent to handle more edge cases, make more decisions, and need less help.

But in mature systems, the goal is the opposite. We want the agent to become more structured, not more free.

This article is part of a series where I walk through how I think about designing agentic systems using a set of practical habits.

Rather than talking about agents in the abstract, I’m using a concrete example throughout the series: a customer support chatbot for a power utility company. This is not a real system and not something I’ve built. It’s a thought exercise designed to surface real design tradeoffs that show up in production systems.

The chatbot helps customers start and stop service, ask billing questions, report outages, request maintenance, challenge bills, apply for rebates, and request refunds. Behind the scenes, it interfaces with identity systems, billing platforms, internal policy documents, regulatory constraints, and operational workflows.

In other words, it looks simple from the outside, and complicated everywhere else.

Across this series, I evolve this system one habit at a time. Each article focuses on a single habit and shows how it changes the way the system is designed, where responsibility lives, and how risk is managed.

This article explores the habit: Progress Through Structure.

In the Agent Habits framework, this habit treats structure, process, and guardrails as enablers of progress rather than obstacles to it.

Autonomy is a vanity metric

Most conversations about agents fixate on autonomy.

How much can the agent do?

How many decisions can it make?

How few humans are involved?

Autonomy is an attractive metric. It is also a misleading one.

Highly autonomous systems are not necessarily mature. They are often just under-constrained.

If your agent can rewrite the SQL query because it “thought it was a good idea,” you don’t have a powerful agent. You have a security breach waiting to happen.

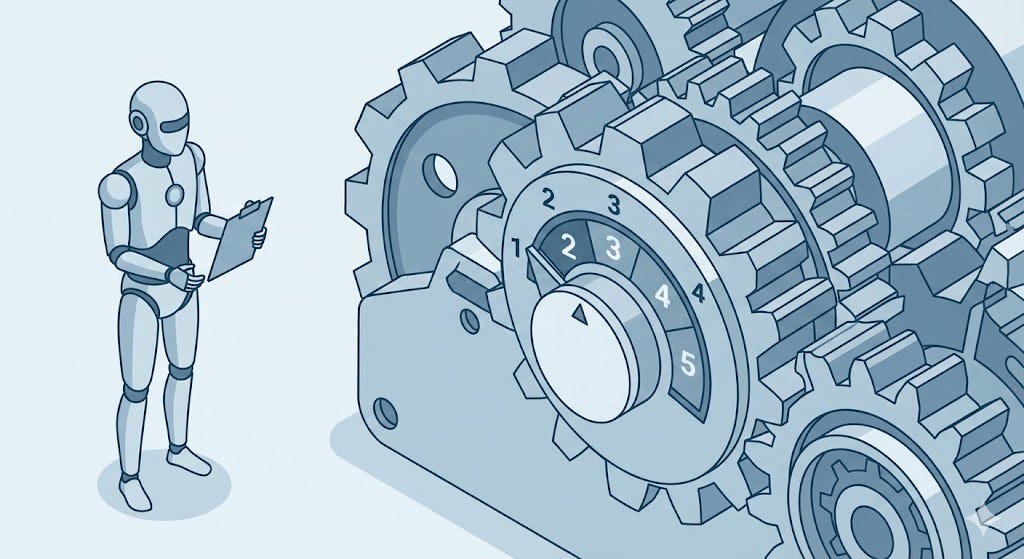

Maturity looks like narrowing

As systems mature, their interfaces should get narrower, not wider.

In our utility chatbot, “progress” doesn’t mean the agent starts improvising legal advice or debugging the mainframe.

Progress looks like Structure:

Clearer Routing: Instead of “guessing” where to send a request, the agent maps user intent to a rigid

WorkflowID.Explicit Playbooks: Instead of generating a response from scratch, the agent fills slots in a pre-approved template.

Harder Boundaries: The agent loses write-access to databases it doesn’t need.

The agent effectively does fewer things, but it does them with absolute reliability.

The Structure Audit

If you want to gauge whether your system is maturing or just expanding, you can start by asking a few simple questions during your design reviews. These aren’t rigid rules, but they often reveal if you are building leverage or just accumulating debt.

Is the prompt getting smaller?

In a new system, the prompt is huge because it contains all the logic. In a mature system, logic moves out of the prompt and into code. If your prompts are shrinking because you are replacing “instructions” with “tools,” you are likely making progress.

Is the interface getting stricter?

Early agents accept “Any String” and return “Any String.” Mature agents require specific IDs, Enums, and Structured Objects. If your agent is still passing raw natural language to a downstream system, there is probably room to tighten the contract.

Is the failure mode boring?

An immature agent fails by hallucinating a believable lie. A mature agent fails by throwing a standard error code (400 Bad Request). If your failures are exciting or creative, you may lack structure.

Applying this to the utility chatbot

Let’s look at two examples of how “Structure” changes the design of our utility bot.

Example 1: The “Junior” vs. “Senior” Agent

The Scenario: The utility company changes the late fee policy from $5 to $10.

The Unstructured Agent: You have to update the system prompt. You have to update the RAG documents. You hope the model weighs the new document higher than its training data. You run 50 test cases. It gets it right 48 times. You pray.

The Structured Agent: The agent doesn’t “know” the fee. The agent knows how to call

get_late_fee_policy().When the policy changes in the database, the agent updates instantly and perfectly.

Example 2: Who owns the checklist?

The Scenario: A customer wants to “Move Service” to a new house. This requires 5 steps: Verify ID, Check Credit, Schedule Disconnect, Schedule Connect, and Confirm Deposit.

The Unstructured Agent: The prompt contains the list of 5 steps. The agent is responsible for remembering where it is in the conversation. It might ask for the deposit twice, or forget to check credit. The “State” lives in the conversation history.

The Structured Agent: The “Move Service” process is a State Machine defined in code, not the prompt. The agent simply asks the system: “What is the next required step for Workflow #123?” The system replies: “Ask for Deposit.”

In the second example, the agent isn’t managing the process; it is just the interface for it. The structure absorbs the complexity, so the agent doesn’t have to.

Predictability is the product

Mature systems behave consistently.

When given similar inputs, they produce similar outcomes.

When they encounter uncertainty, they defer.

When they fail, they fail in known ways.

This is predictability.

Predictability is what allows systems to be trusted, operated, and improved over time. It is boring. And that is the point.

Connecting the habits

Clearly bounded roles define responsibility. Embedded workflows define structure. Permission boundaries define limits. Escalation defines safety.

Progress Through Structure is the realization that these habits are not restrictions. They are the architecture that allows you to scale.

A system that does less, more predictably, is a better system.

What’s next

In the final article of this series, I’ll focus on Visible Accountability.

If an agent makes a decision, we need to know why it happened, who owns it, and how to audit it. Because a system you can’t debug is a system you can’t trust.

The broader habits framework lives here:

https://agent-habits.github.io/