Smart Agents, Broken Systems

Designing Agentic Systems with Good Habits: Optimizes for System Outcomes

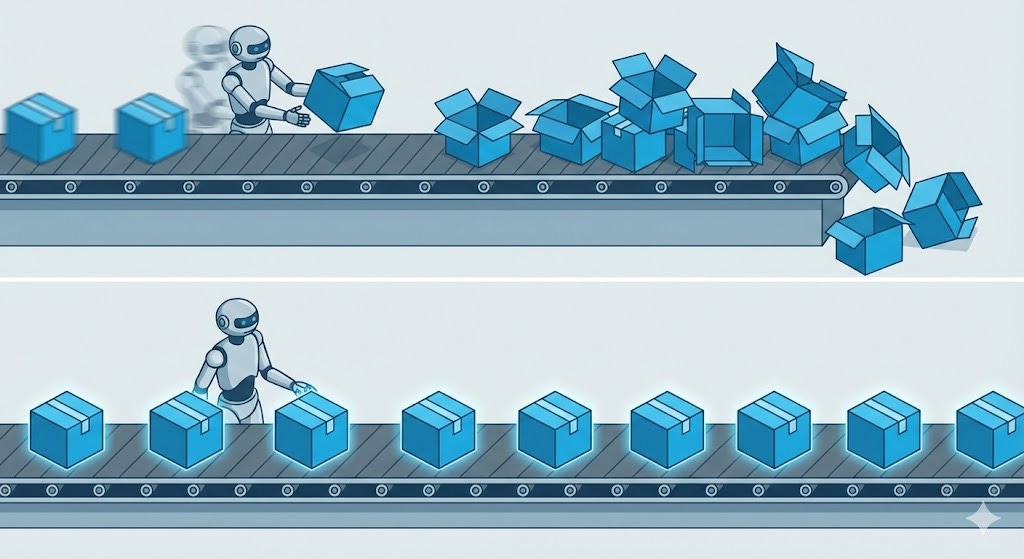

The “Busy Fool” Problem

Agentic systems often fail while looking statistically magnificent.

The agent responds in 200 milliseconds. The “Deflection Rate” is up 15%. The “Sentiment Score” (calculated by another AI, naturally) is glowing. The dashboard is a sea of green arrows pointing up and to the right.

But if you walk over to the customer support floor, the humans are exhausted.

They are drowning in “Tier 2” tickets because the agent gave technically correct but useless answers. They are fixing account data because the agent hallucinated a refund policy. They are soothing customers who were “deflected” right into a dead end.

The problem is not that the agent is slow. The problem is that it is being evaluated on Agent Metrics, not System Metrics.

We have confused “activity” with “value.” An agent that processes 1,000 requests an hour is not an asset if it creates 1,000 follow-up tickets. It is just a high-speed chaos generator.

This article is part of a series where I walk through how I think about designing agentic systems using a set of practical habits.

Rather than talking about agents in the abstract, I’m using a concrete example throughout the series: a customer support chatbot for a power utility company. This is not a real system and not something I’ve built. It’s a thought exercise designed to surface real design tradeoffs that show up in production systems.

The chatbot helps customers start and stop service, ask billing questions, report outages, request maintenance, challenge bills, apply for rebates, and request refunds. Behind the scenes, it interfaces with identity systems, billing platforms, internal policy documents, regulatory constraints, and operational workflows.

In other words, it looks simple from the outside, and complicated everywhere else.

Across this series, I evolve this system one habit at a time. Each article focuses on a single habit and shows how it changes the way the system is designed, where responsibility lives, and how risk is managed.

This article explores the habit: Optimizes for System Outcomes.

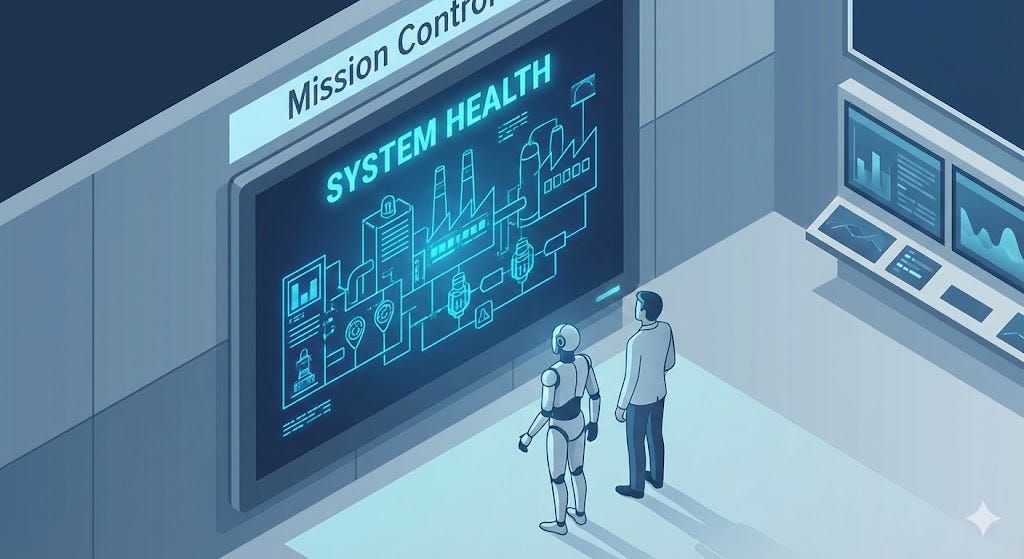

In the Agent Habits framework, this habit prioritizes overall system health and outcomes over local agent efficiency or convenience.

Stop inventing new metrics

There is a temptation, when deploying AI, to invent new ways to measure success. We measure “perplexity.” We measure “tokens per second.” We measure “conversation turns.”

Don’t do this.

If your business measured “Customer Churn” before AI, you should measure “Customer Churn” after AI. If you cared about “Cost Per Resolution” in 2023, you should care about it now.

If you have to invent a new metric to prove your agent is working, it probably isn’t.

Applying this to the utility chatbot

Let’s look at a “High Bill Complaint” scenario and compare two different dashboards.

Scenario: A customer asks, “Why is my bill $400?”

1. The “Smart Agent” Dashboard (Vanity Metrics)

Latency: 400ms (Incredible speed!)

Response Length: 50 tokens (Concise!)

Sentiment Score: 0.85 (Polite!)

Outcome: The agent says, “Your bill is $400 because you used 2000kWh. Mathematical accuracy is 100%.”

The Reality: The customer is furious because you just stated the obvious. They call the support line immediately.

2. The “System Health” Dashboard (Real KPIs)

First Contact Resolution (FCR): 0% (Failed).

7-Day Re-open Rate: 100% (They called back immediately).

Tier 2 Escalation Cost: $15.00 (Human time).

Now, let’s optimize for the System Outcome. The agent slows down. It checks historical usage. It notices a spike. It says: “Your usage jumped 30% in July, likely due to AC. Would you like to switch to budget billing to flatten these spikes?”

Latency: 2.5 seconds (Slower).

Tokens: 150 (More expensive).

7-Day Re-open Rate: 5% (Success).

The second agent looks “worse” on a technical dashboard (slower, verbose). But it actually solved the business problem

.

Metrics shape physics

Agents are optimization machines. They will ruthlessly exploit whatever metric you give them.

If you measure Duration, the agent will rush the user off the chat.

If you measure Deflection, the agent will hide the “Contact Us” button.

If you measure Satisfaction, the agent will apologize profusely instead of fixing the error.

You cannot fix this with “prompt engineering.” You fix it by changing the scoreboard.

Preventing cleverness from becoming harm

This habit exists to prevent the “illusion of competence.”

It forces us to ask: Did the system get healthier?

Did the backlog of tickets shrink?

Did the human operators get to go home on time?

Did the refunds stop leaking?

If the answer is “no,” it doesn’t matter how smart the model is.

Connecting the habits

Clear roles define responsibility. Workflow embedding defines placement. Constraints define limits. Deferral defines risk tolerance.

Optimizing for System Outcomes ensures those design choices actually improve the system rather than just the agent.

Without this habit, agentic systems often get louder, busier, and harder to operate. With it, improvements compound instead of conflict

.

What’s next

In the next article, I’ll focus on Progress Through Structure.

Why the goal of a mature agent isn’t “more autonomy,” but “more predictability.” We will explore why effective systems become more structured over time, not more free.

The broader habits framework lives here:

https://agent-habits.github.io/